|

Today's Opinions, Tomorrow's Reality

Enabler In Chief By David G. Young Washington, DC, June 14, 2022 -- The inflation-fighting mission of the Federal Reserve is being undermined by its support for federal debt financing. When gasoline prices topped $5 per gallon last week, Americans were already in a sour mood. Fuel is just the most visible of many surging prices. May figures show that annual inflation hit 8.6 precent -- the highest since December 1981.1 This makes mockery of politicians' reassurances that inflation is purely temporary, the result of supply chains struggling to catch up with post-pandemic demand. Wishful thinking is partly behind the Federal Reserve's anemic response. In March, it increased interest rates by a mere 0.25 percent, and in May by another 0.5 percent. This leaves them below 1 percent -- well below the 3.5 percent average since the mid-1950s.2 Given the new numbers, many expect bigger increases to come.

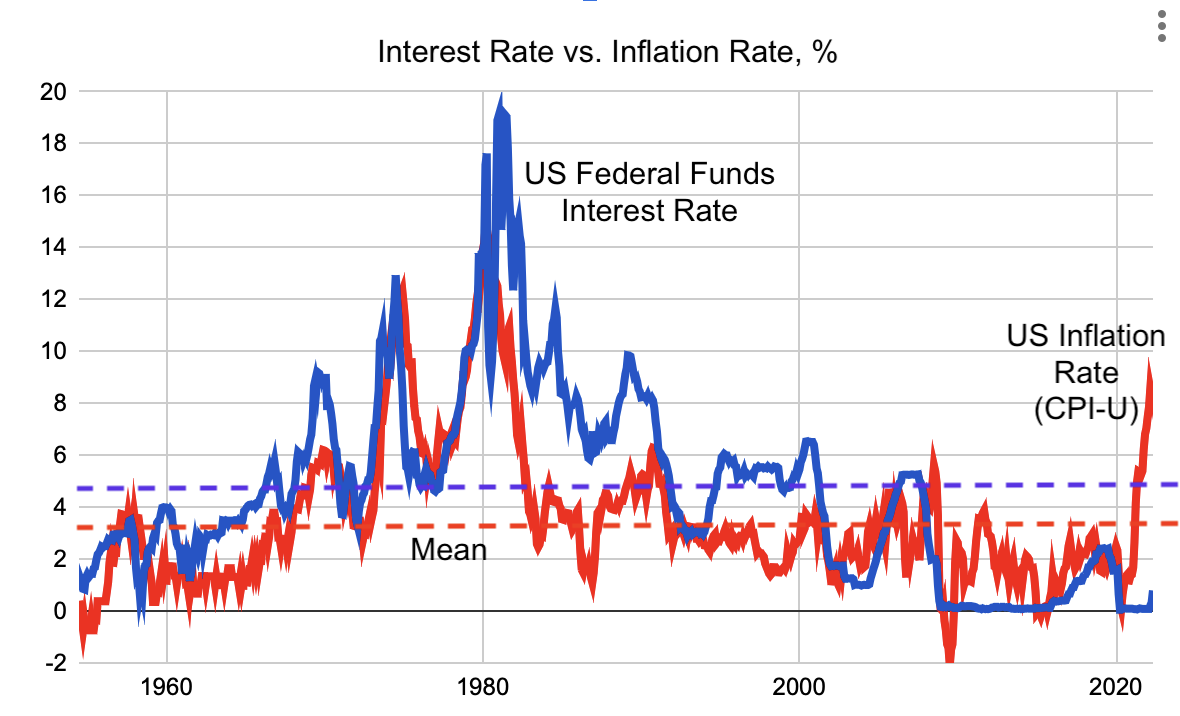

But even if that happens, it begs the question: why has the Fed been so slow to act? A graph of historical inflation vs. interest rates shows the two matching closely for decades, with interest rates typically one percent above inflation. But in recent years the two figures have decoupled. The Federal Reserve has failed to increase interest rates to keep down inflation. Why? Staff economists may spin tales, but today's Federal Reserve has a terrible conflict of interest when it comes to keeping inflation in check. The agency is supposed to raise rates to keep inflation down (so long as unemployment stays low). But that is politically tenuous now that the Fed is the chief enabler of federal government debt. This problem started with the financial crisis. After dropping interest rates to nearly zero, the Fed started "quantitative easing" to support the economy -- effectively printing money. It directly bought government debt (treasury bills and the like) beginning in 2009, and even more so after the pandemic began. The Fed now owns nearly $6 trillion of America's $30 trillion debt3 more than any other entity in the world.

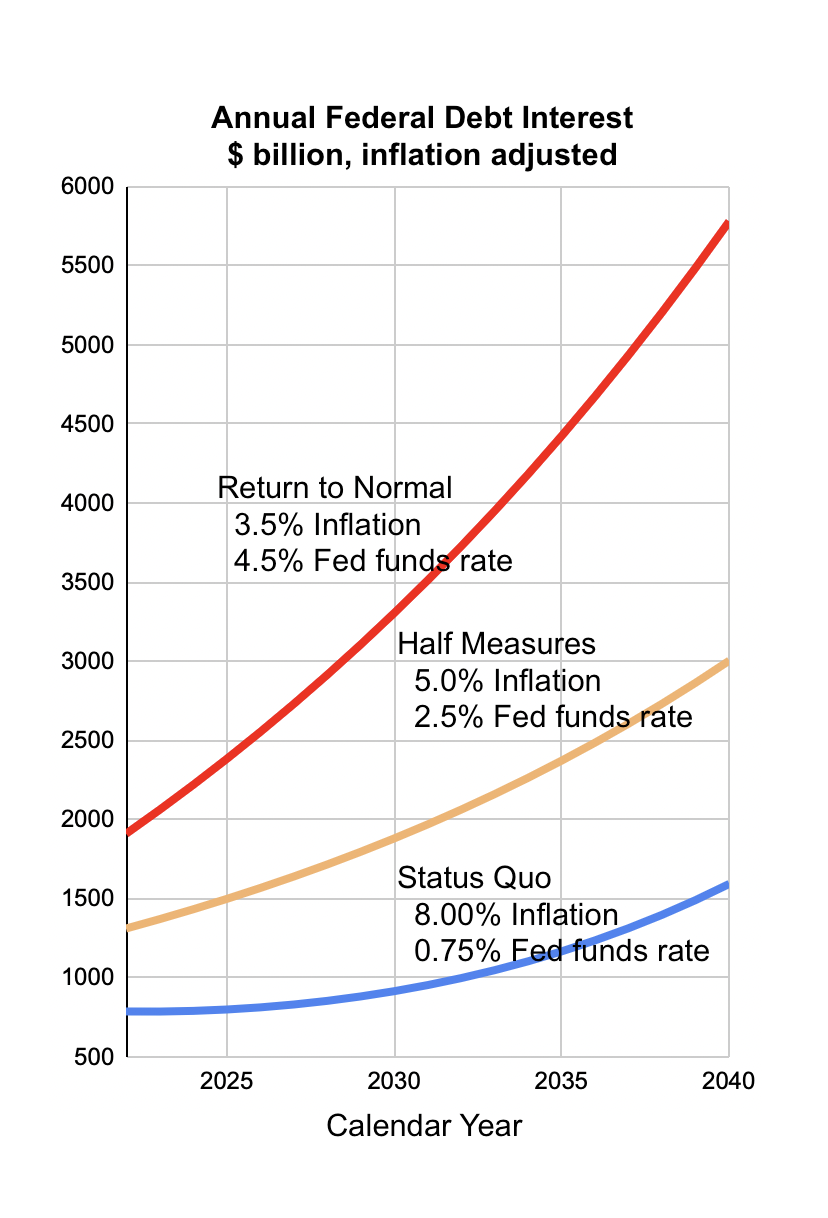

This direct purchase of federal government bonds obviously helps finance its debt. But the Fed also helps it by keeping the interest rates super low. Last year, the federal government paid a stunningly low $562 billion in interest on its enormous $30 trillion debt4. And this undermines the mission of the Fed. The more it raises rates to fight inflation, the more it creates problems for the federal government, which is dependent on those low rates. If the Federal funds rate returns to the historical average of 4.5 percent, debt payments will skyrocket, soon eating up every dollar of taxes the government receives. While the Federal Reserve is theoretically an independent agency, its chairman is appointed by the President and ultimately answers to Congress. Will it be willing to create enormous problems for its bosses? Consider three different scenarios. First, the Federal reserve can "return to normal", raising the federal funds rate to the historical mean of 4.5 percent, hopefully brining inflation down to the historical mean of 3.5 percent. At the other extreme, it can do nothing. It can leave the federal funds rate unchanged at today's crazy low 0.75 percent and let inflation stay high, let's say at 8.0 percent. A third option is to take a middle ground, raising rates to 2.5 percent but no further, hopefully holding inflation to a historically high (but maybe tolerable) rate of 5 percent. You can see the consequences of these three scenarios on federal debt payments in this graph. For simplicity, each scenario assume the approximately $2 trillion non-interest portion of the federal deficit grows only with inflation. The results are telling. If the Fed returns to normal, payments on the federal debt explode because interest rates are so high -- possibly causing a debt crisis. If the Fed does nothing and maintains the status quo, payments on the federal debt increase only slowly (in inflation adjusted dollars) because inflation erodes the value of the debt almost as quickly as deficit spending is adding to it. If the Fed takes the middle ground, the results are somewhere between the two extremes. Independent or not, expect the Fed to try to chart a middle ground. It will raise rates a bit, perhaps bringing inflation down to tolerable but still elevated levels. This may mean that interest rates will stay below inflation rate for years to come. (Sorry savers.) Some will complain this is a violation of the "dual mandate" of the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, which requires the Fed to take action to seek both price stability and maximize employment. But the Fed will probably do it anyway, using creative interpretations to justify its actions. And the President and Congress will probably look the other way. By keeping The Federal Reserve as the chief enabler of deficit spending, politicians can keep popular government goodies flowing to their grateful constituents for several more years to come. Related Web Columns: He Didn't Start the Fire, April 19, 2022 Getting Away With It, October 19, 2019 Coming Drama, March 12, 2013 Living Like There's No Tomorrow, November 9, 2010 From America to Zimbabwe, March 24, 2009 Notes: 1. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, as posted June 12, 2022 2. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Federal Funds Effective Rate, as posted June 12, 2022 3. Federal Reserve, Factors Affecting Reserve Balances, June 9, 2022 4. Voice of America, US National Debt tops $30 Trillion for First Time in History, February 3, 2022 |