|

Today's Opinions, Tomorrow's Reality

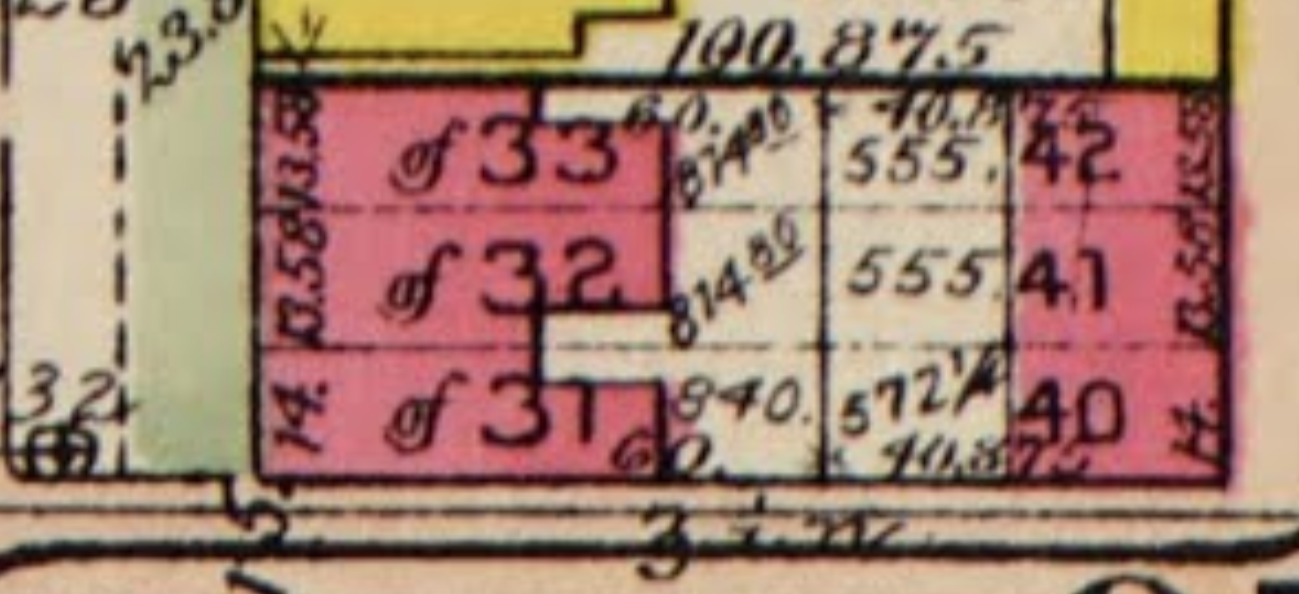

Not in My Backyard By David G. Young Washington, DC, September 17, 2019 -- Elitist opposition to affordable housing has been hurting America's poor for over a century. When President Trump thretened to intervene to tackle the homeless problem in California local politicians did not welcome the move.1 California Legislators had just a day earlier passed legislation imposing state wide rent-control to tackle a housing crisis,2 practically taunting the real estate developer turned president to stick his nose in their business. Just before arriving in Silicon Valley for a fundraiser today, President Trump said California cities are destroying themselves with homelessness.3 Yet Trump hardly needed to travel across the country to witness the problem. Just one mile east of the White House, tent encampments line the western and northern sides of Washington's beaux arts Union Station. Like San Francisco, Washington DC has seen the mentally ill and addicted populations roaming the streets for decades, with a visible increase in addicts on the streets since the opioid epidemic spread to the inner city about three years ago. Skyrocketing housing prices in the capital city have also pushed out residents who can no longer afford rent increases or rising property taxes. Traditional public housing complexes as well as subsidized apartment and townhouse units do exist in Washington. But the share of market-rate units inexpensive enough for working class and poor residents has declined alongside the city's rise to prosperity since the 1990s. This has sharply divided the city between upper-middle class professionals and the underclass either lucky enough to be in subsidized housing or unlucky enough to be out on the street. Washington's housing market has always been driven by boom cycles of jobs flowing from the federal government. Yet it wasn't always so dysfunctional. Over a century ago, in the boom that created the gilded age, Washington DC was the epicenter of an innovative affordable housing system called known as alley dwellings. Unlike government programs that would dominate affordable housing starting with the New Deal, Washington's early system was created by the free market and driven by property developers seeking a profit. Many of the same issues that drove Washington's gilded age housing market are familiar today. There was a high demand for housing in a major job center, but not nearly enough to go around. What was available was unaffordable to poorer residents. The market solution was to increase density by building more smaller homes on the same land. In 1888, Charles Gessford, Washington's biggest developer of the day, started building three homes on a subdivided lot where Sargent James Doddrell had lived across 7th Street from the Marine Barracks4. The new brick rowhouses would be considered luxury units in their day. They had all the modern amenities including gas lighting, running water and and indoor bath,. By October of that year, the housing stock on this land had tripled. But it didn't end there. Two years later, in 1890, Gessford had the lots subdivided again, splitting off the back yards from the three new rowhouses. These back lots faced an alley behind 9th Street where Gessford built three more homes. Unlike the ones facing the street, these were not luxury units -- they were low-cost affordable housing. The tiny homes were less than half the size of the luxury units and had just two rooms with running water, but no gas lighting or indoor bath. Because their front doors faced the back alley, they were known as alley dwellings. The alley units rented for just $7 per month -- less than half the cost of the $15.30 monthly rent of the luxury houses on the street, according to newspaper advertisements of the day. In just two years from 1888-1890, Gessford had increased the available housing stock at 732 9th St SE by six times, half of which was affordable housing. While the less expensive units were smaller, census records showed they typically housed the same number of residents. This pattern was repeated all over the city by Gessford and other developers. Just as today, the new luxury row houses were rented by skilled young professionals working for the federal government -- draftsmen, musicians and the like. But unlike today, these professionals lived side-by-side with unskilled laborers in the alley dwellings. In 1892, a skilled coppersmith named William Thompson rented the fancy townhouse at 730 9th St SE, and an unskilled laborer named Tomas Adams lived in the adjacent alley dwelling.

While this system worked to provide much needed housing, it was extremely unpopular with the city's elite. They considered living in close proximity the poor dangerous, unsanitary and certainly unsavory. Racism undoubtedly played a big part. In a pattern that Washingtonians would find eerily familiar today, all the residents of the luxury units on 9th Street were white and all the residents of the affordable units were black. Wealthier Washigtonians of the day would look out their back windows to see less affluent people visiting the outhouse. It was the ultimate recipe for a “not in my backyard” revolt against the poor. The reaction was swift and severe. In July 1892, the city outlawed further construction of alley dwellings, and activists began campaigning to demolish the units. In 1912, the prestigious Monday Evening Club derided the alley dwellings for "breeding crime and disease to kill the alley inmates and infect the street residents."5 Housing shortages during two world wars delayed these efforts, but before the end of the 1950s, all the alley dwellings behind 7th Street had been demolished, as well as most others across the city. The same arguments levied against the alley dwellings would be repeated nationwide throughout the 20th century to justify urban renewal -- and the end result would always be destruction of less expensive housing. The affordable housing crisis in both Washington DC and California is partly a result of similar slum-clearing efforts. In both places construction of luxury housing continues but new inexpensive housing is almost non-existent. Today's arguments about homelessness in California shows how little has changed in the past century. Developers have long since learned that powerful lobbying by NIMBY residents against low-income housing is far stronger than it is for luxury housing -- and luxury housing is more profitable, anyway. Rather than working to eliminate the ability of NIMBYs and other lobbyists to block affordable developments, politicians focus on easier, feel-good measures that their constituents cheer -- like rent control on the left and police clearing of homeless camps on the right. But the fact is that such measures only focus on symptoms and not the underlying problem. They provide dubious short-term value and no long-term solutions. The real solution to the lack of affordable housing in California and Washington DC is to build more affordable homes. Developers in 1890s Washington found a way to do so and even made a profit along the way. Those who care about housing the less affluent would be well advised to encourage the same today. David G. Young lives in Washington DC in the same rowhouse where William Thompson looked upon Thomas Adams' back yard. The former alley dwelling is now his driveway. Related Web Columns: From Luxury to Squalor, August 26, 2014 Notes: 1. Washington Post, Trump's Proposals to Tackle California homelessness Face Local, Legal Obstacles, September 12, 2019 2. New York Times, California Approves Statewide Rent Control to Ease Housing Crisis, September 11, 2019 3. San Francisco Chronicle, Trump Warns Homelessness is ‘Destroying' SF, Pays Brief Bay Area Visit, September 17, 2019 3. Boyd's City Directory 1881 4. Directory of the Inhabited Alleys of Washington DC, 1912 5. Ibid. |