|

Today's Opinions, Tomorrow's Reality

Worrying Trends By David G. Young Washington, DC, February 21, 2022 -- People who worry about an American debt default should focus not on Congress, but on high interest rates and even higher inflation. As politicians jockey for position over a fight about raising the U.S. debt ceiling, economists warn about the disastrous risks of default. And while there is some theoretical risk from this posturing for political gain, a far more serious risk is quietly building behind the scenes. That real risk comes from skyrocketing costs of debt service by America's federal government, driven by rising interest rates. In the past twelve months, the interest rate on the three month treasury bills has jumped from 0.35 percent to 4.83 percent.1 To understand the consequences of this rate rise, look at consumer mortgages. Most mortgages have fixed interest rates, which give stability in payments, but require paying a somewhat higher rate to banks in return for that stability. But consumers who wish to save money can opt for adjustable rate mortgages. These are common in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, as well as amongst less affluent Americans. But the trick with adjustable rate mortgages is that when interest rates rise, payments periodically reset to the higher rates, causing monthly loan payments to go up significantly. Consumers holding adjustable rate mortgages often face disaster when interest rates spike. Adjustable mortgage rates have more than doubled from 3.18 percent to 6.82 percent in the past year2, potentially doubling some monthly mortgage bills. For many households, this kind of change can ultimately lead to foreclosure or bankruptcy, just as happened in the run up to the financial crisis in 2009. Something similar happens with the federal government. While adjustable mortgage rates typically reset on an annual basis, for the federal government, rates are much more fluid. Every week, the Treasury Department holds auctions for bonds which decide the new interest rate. Bonds that come to maturity are paid out at the old interest rate and new ones are purchased at the new rate set by the auction. The latest auction completed this afternoon, set the interest rate for three month Treasuries at 4.83 percent, the highest rate in over 15 years. As interest rates on the federal debt increase, annual debt payments will start eating a larger share of the federal budget. In 2022, the $475 billion spent on debt service was 8 percent of federal spending.3 But if interest rates stay at current levels, that will slowly rise to over 20 percent as old government bonds paying low rates mature and are replaced by new bonds paying high rates.

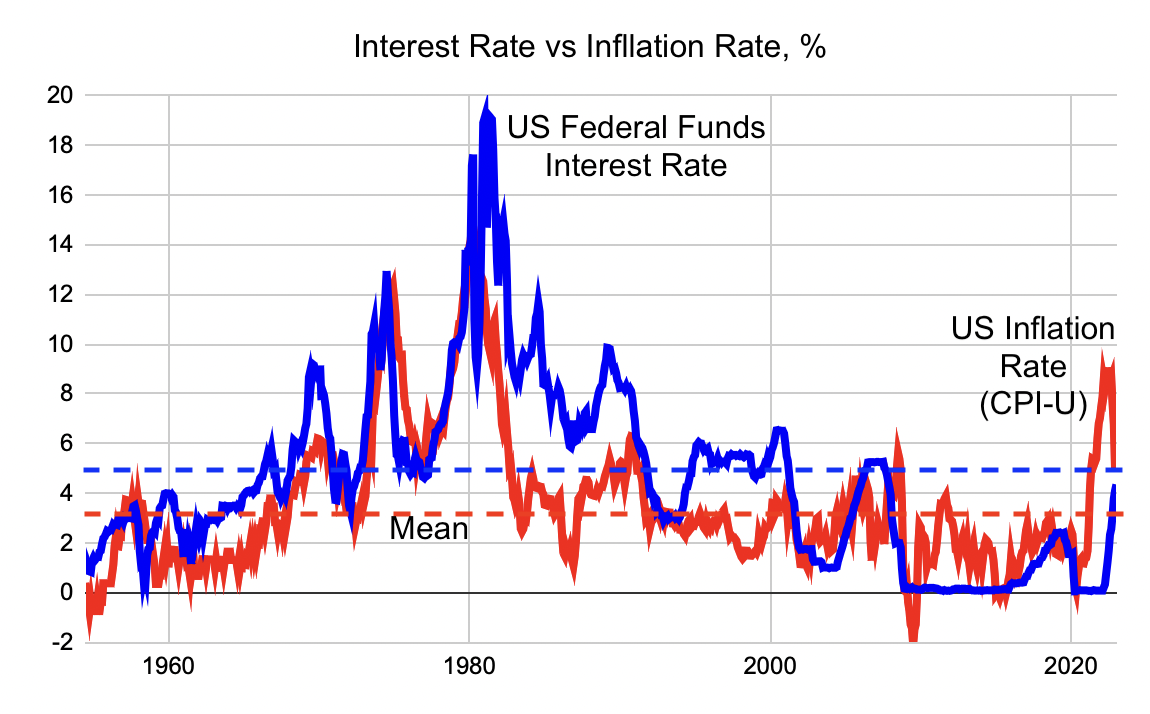

What's worse, since politicians probably won't cut spending in face of these new fiscal realities, the extra debt service costs will end increasing annual borrowing, causing the national debt to grow even faster, the debt service payments to grow even larger, and interest rates to go ever higher as needed to find buyers willing to finance that debt. Like consumers caught up in the subprime mortgage crisis, this could ultimately end in default. If anything can save the federal budget from this grim fate, it's inflation. While the Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates in its bid to fight inflation, these rates have so far stayed below increases in the consumer price index. So long as interest rates remain below inflation rates, the real value of debt in inflation-adjusted dollars goes down over time. In January, the consumer price index was 6.4 percent4, more than two percentage point above the federal funds rate of 4.3 percent. This is not normal. Historically, interest rates are about one percentage point higher -- not lower -- than the inflation rate. But that hasn't been true for the 15 years since the financial crisis. While that's bad new for savers who see the spending power of their money erode over time, it's great news for debtors like the federal government, which sees the real size of its debts go down. Will the lag in interest rates behind the inflation rate continue? Fed Chairman Jerome Powell talks like an inflation hawk who will raise interest rates as needed to eliminate high inflation. Yet late last year he began slowing monthly rate increases from 0.75 percent to 0.5 percent, then to 0.25 percent, despite the fact that inflation continues to remain above the mean and interest rates below the mean. Consider that the last time inflation was this high in the early 1980s, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker quickly raised interest rates several points above the rate of inflation before the problem was under control. So far, Powell has shown himself unwilling to do the same. If inflation is going to come down, this must change. Powell must allow interest rates to return to normal, even if it does mean triggering a federal debt crisis in years to come. Related Web Columns: Enabler In Chief, June 14, 2022 He Didn't Start the Fire, April 19, 2022 Getting Away With It, October 19, 2019 Coming Drama, March 12, 2013 Living Like There's No Tomorrow, November 9, 2010 From America to Zimbabwe, March 24, 2009 Notes: 1. U.S. Treasury Department, Treasury Auction Results, February 21, 2023 2. Nerd Wallet, Current Interest Rates (5 year ARM), as posted February 21, 2023 3. U.S. Treasury Department, U.S. Government Spending, FY 2022, September 30, 2022 4. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index Summary, February 14, 2023 |